Closing the Loop on iOS with Claude Code

Closing the loop means giving Claude Code a way to view the output of its work. I’ll be focusing on iOS app development workflows.

Step 1 of closing the loop: building a target so that Claude Code can see the errors and warnings. And doing so in a way that preserves the build cache (clean builds take a long time). This allows Claude Code to see its syntax errors and fix them before you review its work.

Step 2 of closing the loop: installing & launching on the simulator. This saves you the step of opening Xcode and hitting build & run, letting you test each proposed code change right away.

Step 3 of closing the loop: reading the console & log output. This allows Claude Code to proactively verify codepaths and reactively do debugging.

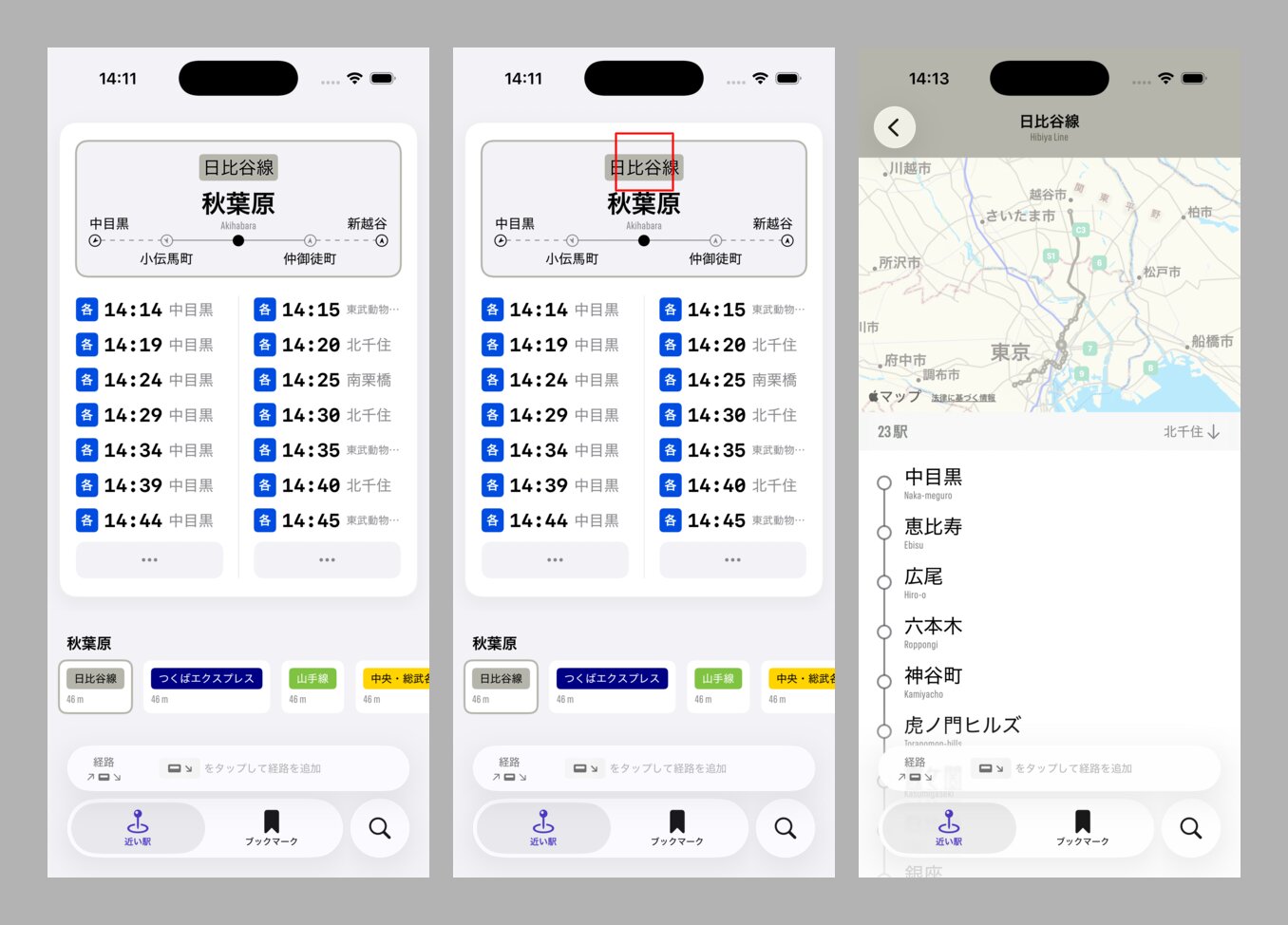

Step 4 of closing the loop: controlling & viewing the iOS simulator. This allows Claude Code to step through entire flows, evaluate visual designs, and generate its own logs.

Step 5 of closing the loop: building, installing, launching, and logging on device. This allows you and Claude Code to test Apple Frameworks that are absent or broken on the simulator.

Disclaimers before we start

Agentic tooling is changing rapidly with model and agent versions. I’ll cover each step as thoroughly as I can. The strategies in this post cover about a month of work in December 2025 with Claude Opus 4.5 inside Claude Code v2.0.76 (and several versions below). I used Xcode 26.1 and 26.2 on macOS 15.7.3 mostly developing for iOS 26.

This post is written for humans but can easily be adapted to a Skill or added to your CLAUDE.md file. The command structure will change based on how your project and schemes are set up. I outline a few different strategies that are useful in different situations, but you may only want to use one workflow as your default, or completely ignore certain steps altogether.

If you’ve always used a manual Xcode-based flow, trying to both understand and incorporate these steps into your workflow can be intimidating. If you’ve never working with Xcode via the command line before, start with just the first step for a while. The best part about this workflow is you can seamlessly dip in and out of using Xcode and there’s no switching cost (not even needing to do clean builds).

The below CLI commands also share a lot of coverage with XcodeBuildMCP, a more full-service MCP-based solution. I won’t get into the pros and cons of MCPs vs CLIs (its author has already written about that).

I’m specifically targeting this post to Claude Code and Opus 4.5 based on my first-hand knowledge of their combined capabilities. Other harness and model pairs will work with most of the commands in this post. The command backgrounding feature in step 3 is the only potential snag for some harnesses.

Step 1: Building

Allowing Claude Code to build after every proposed change is a requirement for agentic workflows. Like it does for human developers, the compiler catches dumb syntax errors and, with Swift concurrency, even data races. The alternative is tabbing back over to Xcode, hitting cmd+b, waiting, copying and pasting error messages into the terminal; a massive waste of human time.

Prerequisites

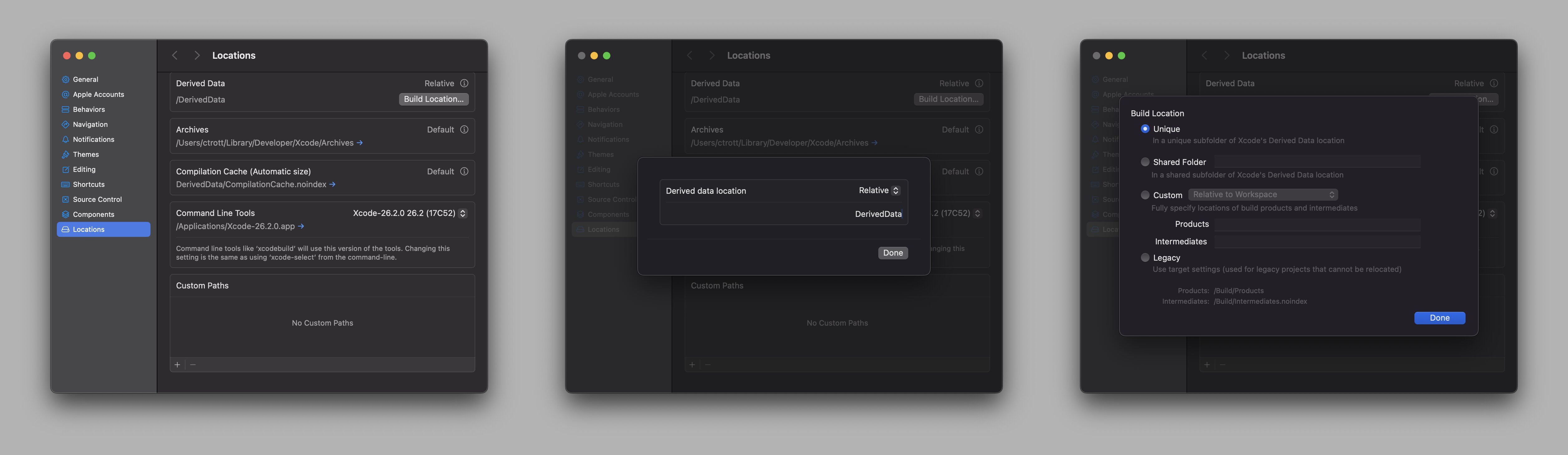

Move DerivedData location to your project folder (optional)

Moving DerivedData to a location inside your project folder is perhaps an unusual suggestion, but it has several benefits for an agentic workflow:

- Permissions: you’ll encounter fewer permissions dialogs when Claude is reading inside the project folder that you’re presumably running it in. Most devs expect DerivedData to be cleared regularly so it’s safe.

- Git worktrees: An advanced technique is to use Git worktrees to have independent copies of your repo. Colocating DerivedData ensures the separate repos don’t interfere with each others build artifacts.

- Docs: The DerivedData has a full copy of your Swift Packages, including any documentation. Claude Code can do fast greps to verify syntax or find examples. In my CLAUDE.md I have a direct link for each important package:

- `DerivedData/train-timetable/SourcePackages/checkouts/swift-composable-architecture/Sources/ComposableArchitecture/Documentation.docc`

- When using Search/Grep/etc. tools, ignore anything in the /DerivedData folder by default unless specifically looking for build artifacts or code/docs for Swift Packages used by this project

Before making this change, add DerivedData/ as a line in your .gitignore file if it’s not already there.

Find the setting in Xcode Settings -> Locations. Set Derived Data to “Relative” and Build Location to “Unique”. It will report /DerivedData as the location.

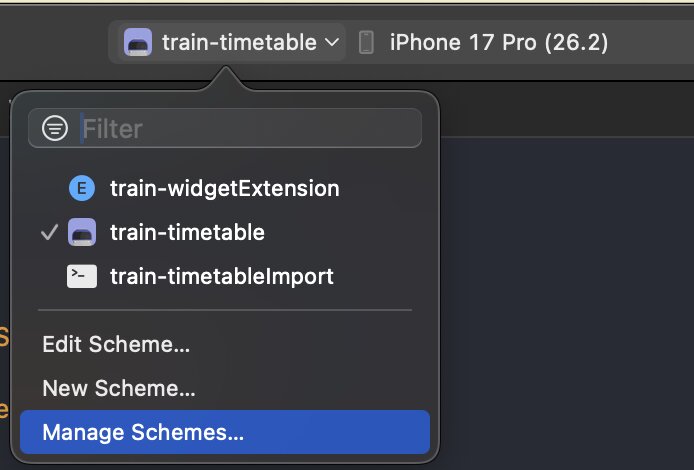

Document project file & scheme

Build commands use your project/workspace file location and scheme name. Claude Code can find these pretty easily with tools but it’s faster to document them in CLAUDE.md.

Get simulators

I’ll assume you’ve already downloaded the iOS simulators and iOS runtime versions you’d like to use in the Xcode interface.

The usual command you’ll use to find the simulator you want produces a very long list, so it’s reasonable to cache your favorite simulator’s UDID so each new Claude Code session doesn’t need do this from scratch each time. “Cache” meaning note it in your CLAUDE.md file, add it as an environment variable, etc.

# Get all available simulators

xcrun simctl list devices available

-- iOS 26.1 --

iPhone 17 Pro (89F6D0BC-E855-4BF7-A400-9C19ED7A7350) (Shutdown)

iPhone 17 Pro Max (F1FA81FA-ED32-40C4-BD78-753254D685AC) (Shutdown)

iPhone Air (77702E5F-85F5-4997-BA14-BC8D8F639B84) (Shutdown)

...

-- iOS 26.2 --

iPhone 17 Pro (DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A) (Booted)

iPhone 17 Pro Max (0C54CF4B-8A45-450E-AB93-B800B97BD4DA) (Shutdown)

iPhone Air (83BECA5F-7894-4705-B198-3DCAE0C4778E) (Shutdown)

...

-- ...

At first, you’ll probably start with a single threaded workflow, having one preferred simulator booted and in use at a time. The below command will output just the UDID for the latest iPhone Pro with the latest installed iOS version.

# Get the UDID of the latest iPhone Pro (non-max) model with the latest available iOS version

xcrun simctl list devices available | grep "iPhone.*Pro (" | tail -1 | grep -Eo '[A-F0-9]{8}-[A-F0-9]{4}-[A-F0-9]{4}-[A-F0-9]{4}-[A-F0-9]{12}'

Once you have more Claudes running in parallel, you’ll can ask each to find its own UDID by looking for a non-booted simulator before it starts building.

Note that even though some commands can be run with more vague identifiers like name, os, or “booted”, it’s much more reliable to select a UDID and use it across commands. For example: specifying "platform=iOS Simulator,name=iPhone 17 Pro" in the build command will pick any simulator that matches, which could be any iOS version. For the build command it’s not as big of an issue, but to ensure predictable runs I recommend using UDIDs only.

Install xcsift

xcsift is a companion parsing library for build output. You’ll be building a lot, and you don’t want to fill up your context with hundreds of lines of “file.swift built”. xcsift solves this by producing just the actionable errors and warnings in json.

brew install xcsift

I add the -w flag to also include warnings in the output. I recommend browsing the xcsift docs to find other flags you might find useful for your project.

Building

OK, after all that setup, we should have all the info we need to assemble the actual build command.

Claude Code will be able to derive and customize the exact build command you need. I recommend doing a quick session with Claude - the goal being to produce a single, always-working command you can document somewhere and use automatically in each future session.

# Example: working build command for a specific simulator

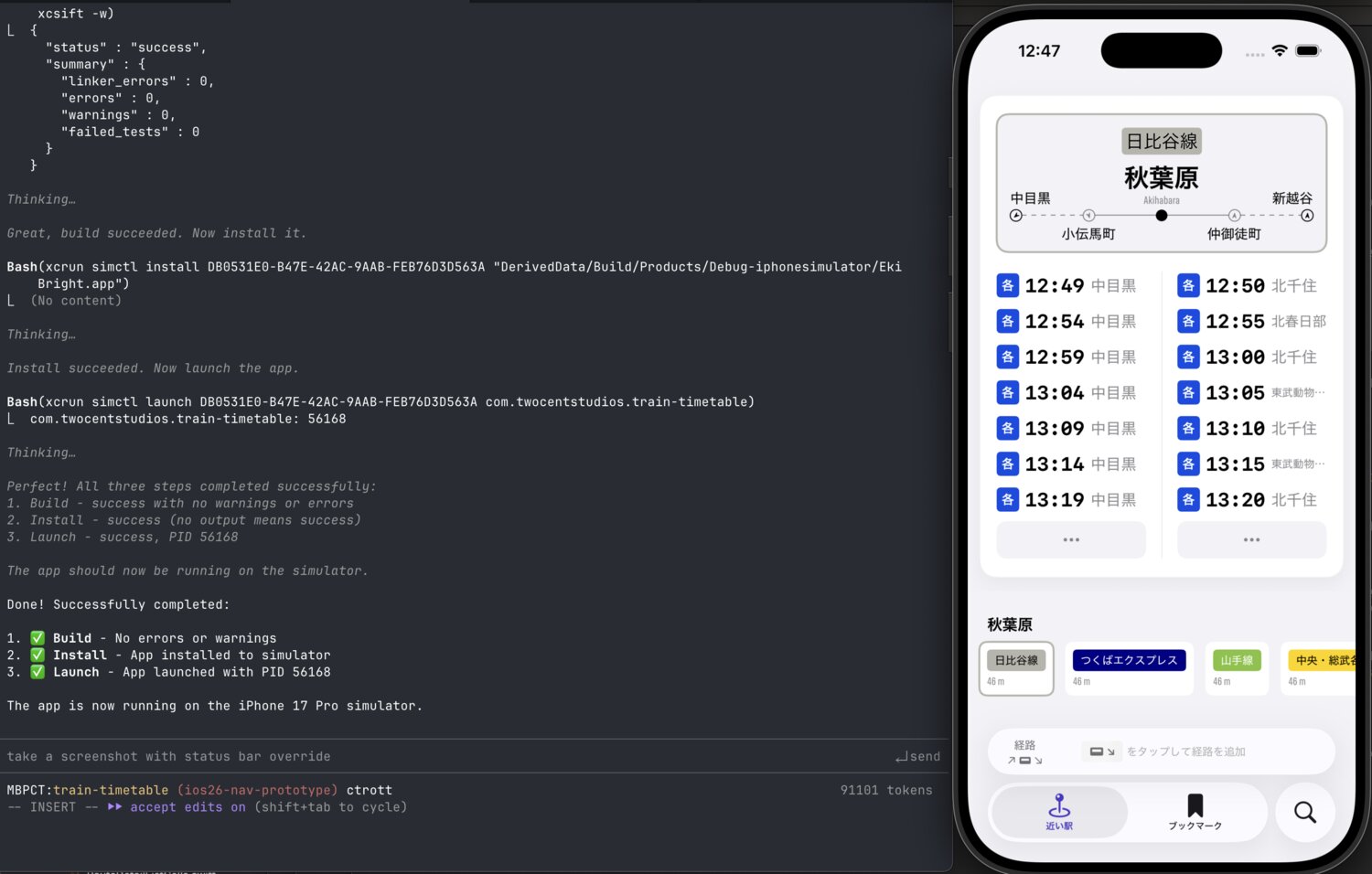

xcodebuild -project train-timetable.xcodeproj -scheme "train-timetable" -destination "platform=iphonesimulator,id=DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A" -derivedDataPath DerivedData -configuration Debug build 2>&1 | xcsift -w

-project: path to your xcodeproj file. Use-workspaceif you use an xcworkspace file.-scheme: scheme name we found above.-destination: for simulator, we use"platform=iphonesimulator,id=$UDID"whereidis the UDID of our favorite simulator instance. Noteplatform=iOS Simulatorhas the same meaning and also works.-derivedDataPath: this is super important if you’ve moved the DerivedData to the project folder. Without this, the Xcode instance will be using a different directory and you’ll have super slow (clean) builds each time.-configuration:Debugis the default, so you don’t usually need this flag. It’s better to be explicit though because this affects the folder where your app binary will be copied to (see step 2).- build: the actual build command

2>&1 | xcsift -w: combines stdout and stderr and pipes them both intoxcsiftso it has access to all output.-wtellsxcsiftto also show build warnings, not just errors.

It’s important to test your ideal build command to confirm:

- It doesn’t force a clean build each time.

- It produces a concise set of errors and warnings.

- It doesn’t interfere with builds via Xcode; you should be able to build/install/run from Xcode, use other SourceKit features, etc. and not clear the build cache.

In my understanding for builds, the simulator UDID (or at least simulator name) does not affect the build artifacts or app binary. However, there’s a lot going on behind the scenes so for simplicity I recommend using the same simulator UDID across all build, install, & launch steps. You need to be careful if running multiple simulators from the same project folder (i.e. without git worktrees) because each build command will overwrite the app binary regardless of whether you run the build command with different simulator UDIDs.

Clearing DerivedData

When left to its own devices (literally), sometimes Claude will get frustrated when a build is failing continuously and it can’t figure out how to fix things. It will sometimes try to remove the entire DerivedData folder. This is a bad idea because 1. clearing DerivedData usually doesn’t fix the underlying problem and 2. it will temporarily break Xcode’s ability to read your Swift packages and you’ll need to restart Xcode to get everything working again.

After I got my build commands more streamlined, Claude stopped doing this as much. But I still have decently strict permissions, so when it does happen, the session will usually block on any rm command and I’ll get a chance to step in and reprimand it. If you run into this problem, you can dig deeper into a configuration-based solution and modify your permissions, add hooks, or add more to your CLAUDE.md. Just something to look out for.

Step 2: Installing & Launching

Building should streamline a lot of your Claude Code workflow. But I slept on the automated install & launch step for too long.

When properly set up with step 1, you should be able to wait for Claude Code to build its changes and return control to you. Then you can tab over to Xcode and hit “run without building” to handle the install & launch.

But when you’re doing build->install->launch dozens of times a day, it’s way more streamlined to check Claude’s session output then tab over to the simulator and tap through screens to test out the changes.

Prerequisites

Document the app binary location for your scheme

Ask Claude to find the location of the app binary produced by the build command.

Since my setup has DerivedData in the project folder and a build directory inside it, that’s where my app binary is: DerivedData/Build/Products/Debug-iphonesimulator/Eki Bright.app.

You’ll notice the folder: Debug-iphonesimulator, which corresponds to our build configuration of Debug from earlier and the platform iphonesimulator. If you go off the beaten path and want to try out a Release build for example, make sure to understand this relationship.

Also be cautious because you want to make sure the most recent build is what you’re installing and launching and looking at. And there’s nothing in the file name that will indicate that.

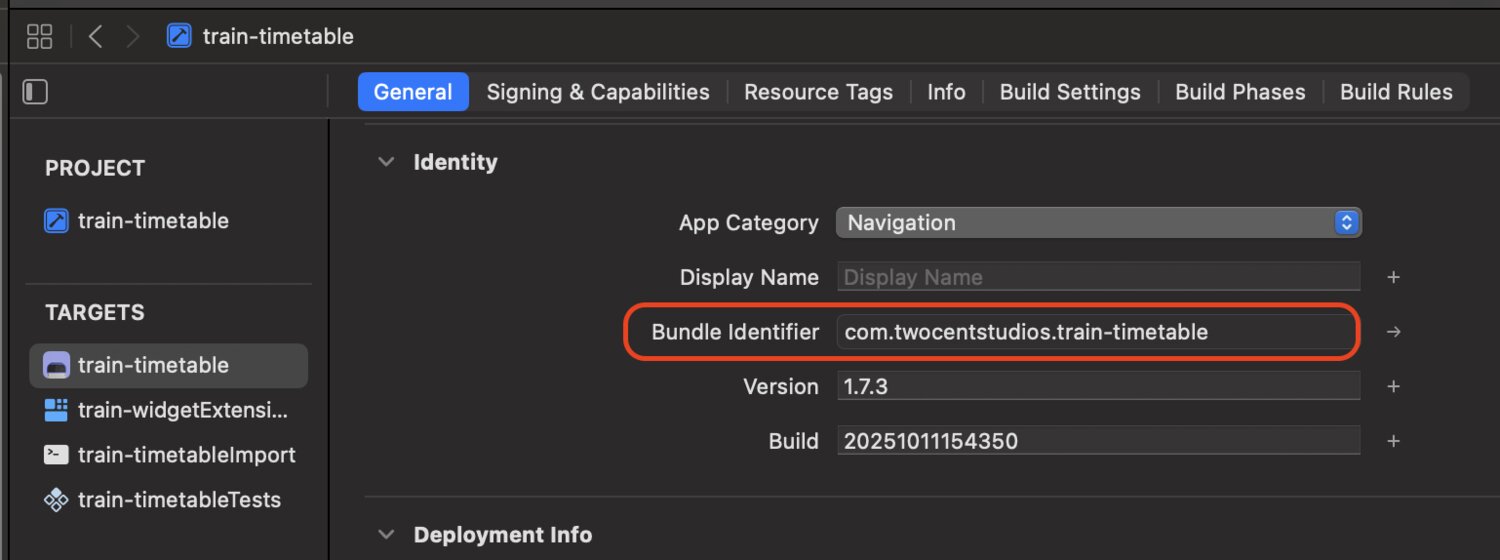

Find your bundle identifier

This will be in your Target’s general settings pane beside Bundle Identifier: com.twocentstudios.train-timetable

Installing the app on the simulator

Installing is copying over the app binary into a specific simulator’s storage. This step depends on the build step having produced an app binary.

The parameters in the install command are:

- UDID: for least headaches this should be the same simulator UDID you specified in the build command.

- path/to/My App.app: the app binary location specified by your scheme.

# Example: install a previously built app binary on the simulator by UDID

xcrun simctl install DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A "DerivedData/Build/Products/Debug-iphonesimulator/Eki Bright.app"

Launching the app on the simulator

Launching the equivalent of tapping your app’s icon in Springboard. It of course depends on the install step having copied over the app binary.

The parameters in the install command are:

- UDID: the simulator UDID you specified in the build & install commands.

- bundle id: apps are uniquely identified by bundle id after installation.

# Example: launch a previously installed app binary by bundle id

xcrun simctl launch DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A com.twocentstudios.train-timetable

Navigating by URL (bonus)

Depending on your app’s navigation structure and pre-existing support for universal links or App Intents, you can save yourself even more time by having Claude automatically navigate the app to the tab, sheet, or navigation destination you’re currently testing.

The full set of caveats is beyond the scope of this post. In my experience, adding Universal Links support without some caution can lead to giving Claude access to data or flows that are impossible for normal app users to see. It may also add maintenance burden for initializers that are only used during debug. Regardless, jumping through a dozen screens automatically can save you hours of unnecessary manual screen-clicking labor.

The parameters for the openurl command are:

- UDID: the simulator UDID you specified in the build & install commands.

- URL: the deep link URL your app knows how to process.

xcrun simctl openurl DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A "train-timetable://tab?name=search"

In my testing, it’s safe to have Claude to run the openurl command immediately after the install command (or even in the same line) without needing a sleep or otherwise waiting for the launch to complete.

Step 3: Reading Console & Log Output

With Step 1, Claude has access to the compiler’s evaluation of its code changes. We can also give Claude access to the console and log outputs so it can evaluate the runtime results.

There are two strategies: console output via print statements and log output via OSLog/Logger. I use both depending on the situation.

Depending on the strategy, we’ll either amend the launch command from step 2 or prepend a CLI command.

Blocking vs. non-blocking

Claude can do blocking and non-blocking for the console variant, and non-blocking-only for the log output.

Blocking means that the prompt input and Claude’s thinking will be suspended until you explicitly stop it or the default timeout (currently 10 minutes) triggers. It will print output from the command inline, but usually truncate portions.

Non-blocking means Claude will use its background capability to keep the command alive and retain access to its output but immediately move the command to the background so that the prompt input is available.

I recommend the blocking flow for when you want to add a few quick print statements to verify a limited (maybe less than 15 seconds) code execution flow that you, the human, are driving in the simulator and have Claude immediately evaluate the results inline. The amount of lines generated should be small, within 10s of lines.

I recommend non-blocking for all other scenarios, including:

- when you want Claude to drive the simulator (discussed in step 4) while monitoring the output.

- when you want to use

Loggerinstead ofprintlogging, probably for more permanent logging code in your codebase. - when you’re expecting to generate dozens or hundreds of lines of logs in a single run. In order to be smart about preserving the session context, you’ll want to write to a file and allow either a subagent to extract meaning from it, or have the primary agent use parsing tools to read only the relevant portions.

--terminate-running-process

Adding the --terminate-running-process flag to launch ensures idempotency by terminating any existing instance of your app and ensuring the app is always cold launched with the console output available.

Adding the --terminate-running-process is super important to the logging flow since you may not be rebuilding and reinstalling between launches.

When you don’t terminate an existing process, the app instance will stay in memory on the simulator. By default, the launch command will not relaunch the app if it’s already launched. This will happen silently. Critically, it will also not read any console output and Claude will get very confused about why nothing is being logged and it will start thrashing and making very dumb changes, ranging from adding more print commands to clearing DerivedData.

(This was my biggest roadblock in getting a reliable and robust debugging flow with Claude; please learn from my mistakes).

Launching the app on simulator and reading the output

Replace the launch commands from step 2 with any of the below variants depending on your use case.

Blocking console/print direct (when you know output volume is reasonable)

Relevant flags and parameters:

--console-pty: produce console print output.--terminate-running-process: as discussed above, ensure the command actually runs.- UDID - the simulator UDID you specified in the build & install commands.

- bundle id - bundle id of the target that produces the app binary.

# Example with simulator UDID and bundle id

xcrun simctl launch --console-pty --terminate-running-process DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A com.twocentstudios.train-timetable

Note: the flags --stdout --stderr do not work. Don’t use them. Use --console-pty instead.

Blocking console/print to file (safer for unknown or expected heavy output)

Relevant flags and parameters:

--console-pty: produce console print output.--terminate-running-process: as discussed above, ensure the command actually runs.- UDID: the simulator UDID you specified in the build & install commands.

- bundle id: bundle id of the target that produces the app binary.

- output file path: the plain text file console output will be written to. Note: I write to a tmp folder within DerivedData to ensure Claude has access to the result without triggering unnecessary permissions dialogs.

2>&1: ensure stdout & stderr both end up in the file.

xcrun simctl launch --console-pty --terminate-running-process DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A com.twocentstudios.train-timetable > DerivedData/tmp/console.log 2>&1

Non-blocking console/print

Non-blocking requires using Claude Code’s run_in_background parameter on the Bash tool. This will produce a task_id that Claude can later use to get the output (from an implicitly created text file) and kill the task.

After running the Bash tool, the prompt will be unblocked and you can ask Claude to monitor the output or ask it do anything else you want.

The non-blocking flow requires a bit more ceremony; you’ll need to tell Claude when you’re done working with the simulator and it should analyze the results. It usually leaves the background task running (potentially writing log data to the output), so you’ll need to specifically tell it to stop.

The command itself is the same as the one from Blocking console/print direct.

Bash(

command: "xcrun simctl launch --console-pty --terminate-running-process DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A com.twocentstudios.train-timetable",

run_in_background: true

)

Command running in background with ID: b8e2ca5.

# *wait for next user prompt*

TaskOutput(task_id: "b8e2ca5")

KillShell(shell_id: "b8e2ca5")

Non-blocking Logger/OSLog

With only its training data, Claude knows how to use Logging by importing the OSLog framework. OSLog has strengths and weaknesses compared to console/print logging. You may already be using it in your app. I consider it more of a long term solution you’d add to your codebase alongside each feature and keep it up to date with any changes.

Giving Claude access to these logs is different from the print/console flow we just discussed.

The root command is xcrun simctl spawn.

spawn log stream only captures logs emitted while it’s running (not before). If you want logs starting from launch, always run it before the launch command.

Blocking on spawn log stream doesn’t make sense because you still need to launch the app. You should dispatch it directly to the background as non-blocking.

Relevant flags and parameters (Claude knows how to adjust these freely):

- UDID - the simulator UDID you specified in the build & install commands.

--level: matches the log level in your code;debug,info,warning,error, etc.--predicate: filters the firehose output the messages you’re interested in. Lots of options here depending on how you’ve definedLoggers and added log statements in your codebase.

After spawn log stream is dispatched to the background, you’ll need to launch the app with the launch command. You can choose a blocking or non-blocking launch command.

Note that the raw spawn log stream command is not actually monitoring the specific app process. You can start this early in your session, cast a wide net, and keep this running through your whole session, asking Claude to filter the relevant time periods from the output. I personally haven’t needed this flow though.

Bash(

command: "xcrun simctl spawn DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A log stream --level=debug --predicate 'subsystem == "com.twocentstudios.train-timetable"')"

run_in_background: true

)

Command running in background with ID: b8e2ca5.

Bash(xcrun simctl launch --terminate-running-process DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A com.twocentstudios.train-timetable)

# *blocking prompt until user escapes*

TaskOutput(task_id: "b8e2ca5")

KillShell(shell_id: "b8e2ca5")

Non-blocking console/print & Logger/OSLog

You can combine everything above and give Claude access to both console/print output and Logger/OSLog output. The launch command can be blocking or non-blocking, but the below example is non-blocking.

Bash(

command: "xcrun simctl spawn DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A log stream --level=debug --predicate 'subsystem == "com.twocentstudios.train-timetable"')"

run_in_background: true

)

Command running in background with ID: b8e2ca5.

Bash(

command: "xcrun simctl launch --console-pty --terminate-running-process DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A com.twocentstudios.train-timetable",

run_in_background: true

)

Command running in background with ID: a792db1.

# *wait for next user prompt*

Step 4: Controlling & Viewing the iOS simulator

Giving Claude eyes and virtual fingers to see and control the iOS simulator is where we start to reach the avant-garde. At the current (end of 2025) model & harness capabilities things start to go off the rails pretty quickly. I wouldn’t expect great results from Claude at tasks related to manipulating the simulator like a human, but in certain scenarios, the benefits outweigh the costs.

Prerequisites

AXe

AXe is a comprehensive CLI tool for interacting with iOS Simulators using Apple’s Accessibility APIs and HID (Human Interface Device) functionality.

Claude can use AXe to manipulate the simulator through taps, swipes, button presses, and keyboard typing.

Under the hood, AXe uses Facebook’s idb CLI.

Install AXe with Homebrew.

Image Magick (optional)

ImageMagick® is a free and open-source software suite, used for editing and manipulating digital images.

Claude can use ImageMagick to do some post-processing on screenshots from the simulator.

Install ImageMagick with Homebrew.

FFmpeg (optional)

Claude can use the venerable FFmpeg CLI for advanced video manipulation use cases. You may not need it but there’s a good chance you already have it.

Reading from the simulator

In order to navigate the simulator beyond the universal links openurl use case we detailed above, Claude needs to be able to see the current state of the simulator.

There are 3 options for this:

- Accessibility info - Claude can read a hierarchical text description of the current screen using accessibility info.

- Screenshots - Claude can take a screenshot of the simulator and use the

Readtool to access its multimodal capabilities. - Video - Claude can record a short video capture of the simulator, slice it up into frames, and read a few to assess an animation.

Accessibility info via describe-ui

The AXe command for getting the accessibility trace is:

axe describe-ui --udid SIMULATOR_UDID

...

{

"frame": {"y": 82, "x": 346, "width": 36, "height": 36},

"AXLabel": "閉じる",

"type": "Button"

}

...

The output is a big JSON array.

I thought Claude would be better at understanding and navigation with text information than image information, but in practice it almost always ignored my instructions in CLAUDE.md to use describe-ui before the screenshot flow. Perhaps there’s something in the system prompt or it’s less efficient to hunt through all the text.

I also immediately ran into a reported issue in AXe and idb where describe-ui does not print tab or toolbar info, perhaps only from iOS 26. This makes it very difficult to deterministically do any sort of navigation from the root in many apps.

All this is to say that, at the moment, it’s more reliable to use screenshots.

Screenshots

Claude can use simctl to get screenshots.

Like the other commands, I prefer to write to a tmp folder within DerivedData.

Screenshots for most simulators are taken at 3x scale, but input taps and swipes are at 1x. For the dual purposes of 1. reducing the amount of calculation required to translate screen position to next tap position and 2. reducing the amount of image data that needs to be sent to and processed by Claude, I automatically resize all screenshots to 1x via magick.

xcrun simctl io DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A screenshot DerivedData/tmp/screen.png && magick DerivedData/tmp/screen.png -resize 33.333% DerivedData/tmp/screen_1x.png

Video

Reading live or even recorded video is currently beyond Opus 4.5’s capabilities. I’m guessing this will be a supported flow sometime in 2026, but until then analyzing video output of the simulator is still at proof-of-concept maturity.

While I was debugging a tricky animation, I gave Claude some leash to test whether it could:

- start recording a short clip immediately before a tap.

- stop the recording after 2 seconds.

- use FFmpeg to grab 5 or 6 frames spaced out across the video.

- read the frames and analyze the motion.

It sort of worked? Not really? If you have a use case, you can try experimenting more with this flow. For now I’d consider the actual animation analysis a human-only endeavor. But Claude can still help get the simulator staged up to the start screen.

I believe I used this AXe command as a Claude Code background task:

axe record-video --udid DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A --fps 30 --output DerivedData/tmp/recording.mp4

Manipulating the simulator with taps and swipes

AXe has a variety of tap and gesture commands. Claude can tap on points or accessibility labels.

# Tap at logical coordinates (use frame center from describe-ui)

axe tap -x 201 -y 297 --udid DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A --post-delay 0.5

Without additional guidance, Claude gets confused about which scroll command maps to what logical direction.

# Scroll (named by finger direction, not content direction)

# scroll-up = finger UP = content UP = see content BELOW = triggers .onScrollDown

# scroll-down = finger DOWN = content DOWN = see content ABOVE

axe gesture scroll-down --udid DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A --post-delay 0.5

axe gesture scroll-up --udid DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A --post-delay 0.5

It’s useful to note the swipe-from-left-edge gesture because it’s the quickest way for Claude to pop back a level in a NavigationStack.

# Edge swipes (for back navigation, etc.)

axe gesture swipe-from-left-edge --udid DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A --post-delay 0.5

Strategies for increasing tap accuracy

The most significant source of indeterministic behavior is in Claude’s ability to accurately measure of coordinates on screen. In other words, it can’t read an image and always find the center point of a button. This means there is plenty of opportunity for situations like:

- Claude reads a screen and wants to tap a button.

- Claude makes a bad guess and taps above the button.

- Claude reads the screen again. There was no change.

- Claude makes another bad guess and taps below the button.

Claude’s only feedback about whether its tap was successful is based on its next screenshot. This can lead to situations where it gets irrecoverably lost while navigating your app:

- Claude reads a screen and wants to tap a button.

- Claude makes a bad guess and taps above the button, hitting a completely different button.

- Claude reads the screen again.

- Claude sees it’s on a different screen than expected and becomes confused.

I came up with an experimental flow to try to improve Claude’s accuracy, but:

- It slows down the entire process by 2x.

- By the time Claude realizes it needs to use the experimental flow, it’s already too far lost to recover.

Regardless, my flow, also using ImageMagick, is to make Claude draw a red circle on a screenshot in its targeted tap location before actually performing the tap:

- Take screenshot and resize to 1x (so pixels = points):

xcrun simctl io DB0531E0-B47E-42AC-9AAB-FEB76D3D563A screenshot DerivedData/tmp/screen.png && magick DerivedData/tmp/screen.png -resize 33.333% DerivedData/tmp/screen_1x.png - Read the 1x image and estimate target element center in points

- Verify guess by drawing a red box at those coordinates:

magick DerivedData/tmp/screen_1x.png -fill none -stroke red -strokewidth 2 -draw "rectangle $((X-30)),$((Y-30)) $((X+30)),$((Y+30))" DerivedData/tmp/screen_marked.png - Read marked image to check if box is on target

- If missed, adjust coordinates and repeat from step 3

- If correct, tap at the verified coordinates

Putting it all together

So far in practice, I’ve used this capability alongside universal links to fix and verify simple visual bugs. I have Claude craft input to reproduce the error and find the screen where it occurs, take a “before” screenshot, implement the fix, build/install/launch, then find the same screen, verify the fix, and take an “after” screenshot.

It takes way longer for Claude to do than me, but it’s mostly tedious work, and I’m usually in another tab working on a plan with another Claude. When I come back and see the before and after screenshots alongside the code change, I can feel confident in Claude’s work.

Step 5: Building, Installing, Launching, Reading Output on a Physical Device

Finally, for those Apple SDKs that only work on device, for ensuring observed buggy behavior isn’t just a simulator quirk, or just to get a more realistic look at our apps in context, we can implement steps 1, 2, and 3 on a physical device. Unfortunately, as far as I can tell, there’s no way to control a physical device via CLI tool, so step 4 is out reach for now.

However, building, installing, launching, and logging can still save some time and annoyance during iterative debugging sessions. It’s especially useful to have Claude help analyze logs for (underdocumented) frameworks like Core Location that behave wildly different on a real device than on the simulator.

Below is a collection of tested CLI commands for doing all the above tasks on a physical device.

Note that in my testing all the relevant commands below work equally for devices on the same network and devices connected directly to your Mac via USB.

Prerequisites

Get devices

The device Name and Identifier are both important for on-device debugging. State will be available when Wi-Fi debugging is available, and connected when directly connect via USB.

# Get all connected devices

xcrun devicectl list devices

Name Hostname Identifier State Model

----------- --------------------------- ------------------------------------ ------------------ -------------------------------------

CT's iPhone CTs-iPhone.coredevice.local ABCDEF01-1111-5555-AAAA-F7D81A900001 connected (no DDI) iPhone 14 Pro (iPhone15,2)

CT’s iPad CTs-iPad.coredevice.local ABCDEF01-2222-6666-BBBB-F44A19F00002 available iPad Pro (11-inch) (iPad8,1)

CT’s iPad CTs-iPad-1.coredevice.local ABCDEF01-3333-7777-CCCC-D33889000003 unavailable iPad mini (5th generation) (iPad11,1)

Some example use cases for parsing out values in one go:

# Get the Identifier of the first accessible iPhone (WiFi or USB)

xcrun devicectl list devices | grep "iPhone" | grep -E "(available|connected)" | head -1 | grep -Eo '[A-F0-9]{8}-[A-F0-9]{4}-[A-F0-9]{4}-[A-F0-9]{4}-[A-F0-9]{12}'

ABCDEF01-1111-5555-AAAA-F7D81A900001

# Get the name of the first accessible iPhone (WiFi or USB)

xcrun devicectl list devices | grep "iPhone" | grep -E "(available|connected)" | head -1 | awk -F' +' '{print $1}'

CT's iPhone

Build for device

Build commands are the same as those for the simulator, except platform=iOS instead of platform=iphonesimulator/platform=iOS Simulator.

Use the name of your target device from the list devices command.

# Using device name

xcodebuild -project train-timetable.xcodeproj -scheme "train-timetable" -destination "platform=iOS,name=CT's iPhone" -derivedDataPath DerivedData build 2>&1 | xcsift -w

Note: platform=iphoneos does not work. id instead of name does not work.

Install on device

Install commands use devicectl but are the similar to those for the simulator, except --device should use the device ID, and the build product directory should use Debug-iphoneos instead of Debug-iphonesimulator.

xcrun devicectl device install app --device E7E3E660-9E7A-5814-8BBB-F7D81A965CEB "DerivedData/Build/Products/Debug-iphoneos/Eki Bright.app"

Launch on device

The vanilla launch command is below. I again recommend using --terminate-existing, the device equivalent of the simulator’s --terminate-running-process.

xcrun devicectl device process launch --device E7E3E660-9E7A-5814-8BBB-F7D81A965CEB --console --terminate-existing com.twocentstudios.train-timetable

Blocking console/print capture on device

For console/print capture, use the launch command above with the --console flag. It works over USB and Wi-Fi.

xcrun devicectl device process launch --device E7E3E660-9E7A-5814-8BBB-F7D81A965CEB --console --terminate-existing com.twocentstudios.train-timetable

Non-blocking console/print capture on device

# Use run_in_background: true on Bash tool

# Works over USB and WiFi

Bash(

command: "xcrun devicectl device process launch --device E7E3E660-9E7A-5814-8BBB-F7D81A965CEB --console --terminate-existing com.twocentstudios.train-timetable",

run_in_background: true

)

Command running in background with ID: b8e2ca5.

# *wait for next user prompt*

TaskOutput(task_id: "b8e2ca5")

Logger/OSLog capture on device (requires manual sudo)

A downside of OSLog is that it requires sudo and Claude Code can’t use sudo commands directly. There are presumably some ways to give Claude this capability in more a dangerous fashion. But a safer workaround for now is for you, the human, to run the below commands in another terminal tab. Claude can give you the full command to copy/paste into the other terminal.

Another downside is that the process is slow and produces lots of logs.

These commands will produce groups of files that Claude can read.

Note that the log collect is of everything on the device in the past, and can quickly balloon to gigabytes of storage. The command to collect even the last 2 minutes of logs can take about 30 seconds to complete on Wi-Fi.

Content filtering with --predicate is not supported: Warning: --predicate is ignored when collecting from attached device.

Claude will handle filtering while reading/analyzing with log show --predicate ....

The most logical way to use this is to:

- have Claude build, install, and launch the app on your device (ensure it’s unlocked), and have it note the start time.

- tap around and do the testing you need in order to generate the logs you want.

- have Claude give you the

sudo log collectcommand with a start time a little before the launch time. - run the

sudo log collectcommand in a separate terminal window, enter your password, wait ~1m for it to finish. - ask Claude to analyze the log archive.

# Human user must run these commands in another terminal tab (Claude Code can't provide sudo password)

# `--last` collects from N minutes before the command was run

sudo log collect --device-name "CT's iPhone" --last 2m --output DerivedData/tmp/device-logs.logarchive

# `--start` collects from the specified start time until the command was run

sudo log collect --device-name "CT's iPhone" --start "2025-12-30 16:11:00" --output DerivedData/tmp/device-logs.logarchive

# Then analyze with log show (Claude can do this)

log show DerivedData/tmp/device-logs.logarchive --predicate 'subsystem == "com.twocentstudios.train-timetable"'

Note --device-udid does not work, use --device-name instead - log: failed to create archive: Device not configured (6).

Note --size does not (seem to) work either.

Final thoughts

How to parameterize names, ids, etc. for these commands

So far, I’ve just been hardcoding these commands with my favorite simulator UDID and project path into my CLAUDE.md. When a new version of Xcode comes out I ask Claude to update all mentions of the UDID to the most recent simulator version and it only takes a minute. Hardcoding these values leaves the least room for hallucination. When running these commands dozens of times a day, you really want consistency.

Other ways to handle this would be:

- set environment variables at some level.

- add a start hook to have Claude fill in the environment variables fresh for each session.

- set up another layer of orchestration that handles the pool of simulators and dispatches an ID to each new Claude instance that requests one.

These are all beyond the scope of this post. If you work primarily on one project with others, you probably already have some tooling for specifying the Xcode version, etc.

Why not include traditional testing?

Arguably, TDD was the original “closing the loop” in software development. TDD has never caught on in the iOS world.

I dabbled with an actual Swift Testing-based testing flow for another recent project, and even wrote about another experimental system a few months ago in Giving Claude Code Eyes to See Your SwiftUI Views that used snapshot testing. What I found was although tests are great for verifying correct behavior over the long term, in the short term they are super slow on iOS:

- Installing and launching requires instantiating a brand new simulator for each run (e.g.

Clone 1), which takes a long time. - All builds are clean builds (this could have just been a fluke in my setup at the time though).

- Swift Testing does not output failures in a way that Claude can read and iterate on (again, potentially solvable).

Admittedly, I didn’t spend as much time debugging these flows. Hopefully someone else will fill in the blanks for testing and write this guide.

Don’t sleep on simctl

The simctl CLI we’ve used throughout this post has a ton of other abilities that Claude can use to make our lives easier. This includes adding images to Photos, changing the system time, changing the system language, resetting privacy, resetting the keychain, and many more.

Ask Claude to configure your simulator on the fly instead of clicking through settings with your mouse.

What does the future hold?

I’m honestly not sure how long the hard-won knowledge in this post will be relevant, given the pace of model & harness capabilities. Peter Steinberger already says Codex is good enough and doesn’t need any additional guidance about build commands or working with the simulator.

I can definitely see a world where Claude Code has a live feed of the simulator output it can process and react to at 60 fps, tapping and swiping with full accuracy. This is probably what’s missing in fully closing the development loop on iOS. Doing the same for a real device hopefully isn’t close behind.

At that point though, I’m not sure what else about development will have changed.

Going forward

Most of the material in this guide has been slowly compiled over the month in my various CLAUDE.md files. It was great getting a chance to formalize it even if I can’t make a quickly installable Plugin or Skill to share (hopefully you understand why after reading the post). I’m looking forward to seeing how far I can take each of these steps in the near future.

Corrections

Please reach out if you find any corrections or can contribute any additional knowledge or edge cases.