Shinkansen Live - Developing the App for iOS

In my last post I introduced the motivation and feature set of Shinkansen Live, my latest iOS app. I encourage you to read that one first to learn about what the app does.

In this post, I’ll discuss a few of the interesting development challenges I faced during its week of development from concept to App Store release.

Contents

- Overall development strategy

- OCR and parsing the ticket image

- Live Activities

- Animations

- AlarmKit

- Localization

- Dynamic Type

- VisionKit Camera

Overall development strategy

I created an Xcode project myself with Xcode 26.1 (later switching to Xcode 26.2), then added the TCA package.

Then, I set off to work using Claude Code with Opus 4.5. I started by having it lay out the SwiftUI View and TCA Feature without any logic. Then I built out the rest of the infrastructure around getting the input image, doing OCR, parsing the output, and displaying the results. I’ll go through more of the history later on in the post.

OCR and parsing the ticket image

The most difficult part of getting this app to production was the ticket OCR & parsing system. This system went through the most churn over the week, partially due to expanding scope and partially due to my expanding understanding of the problem space.

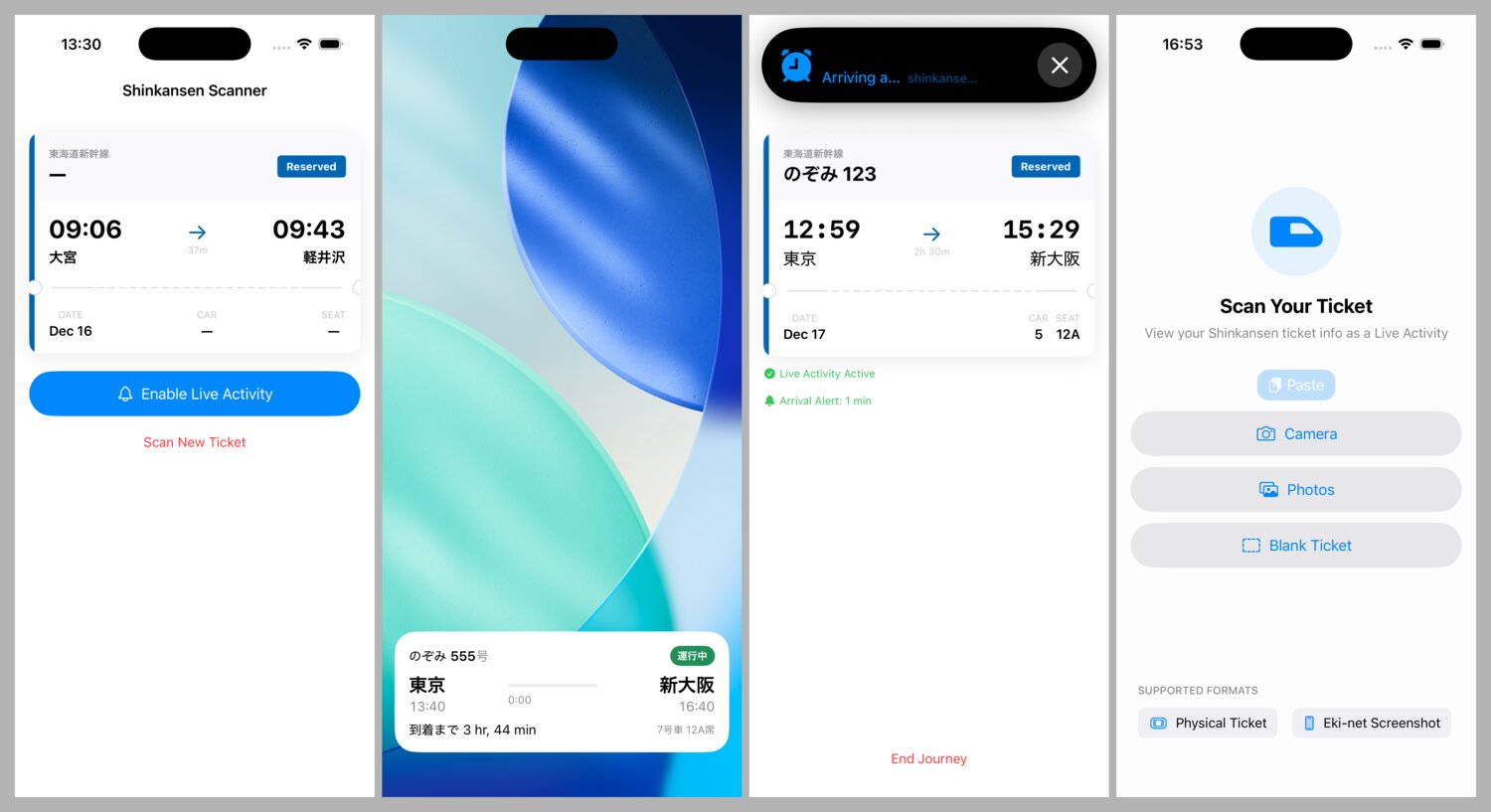

My initial thought during the prototyping stage was to target only the “ticket” screenshot from Eki-net you get after purchase. It looks something like this:

In theory, it’d be reasonable to limit the app’s input space to app screenshots from Eki-net (JR-East) and SmartEX (JR-central). Even including web browser screenshots wouldn’t be that much more burden on an OCR-based system. But later on in the project when I’d decided I was happy enough with the prototype that I wanted to target a production release on the App Store, I started thinking about how it would make marketing much harder to say “only works on screenshots” and not physical tickets.

Why OCR? Why not multi-modal LLMs?

OCR via VisionKit alongside manual parsing has a lot of upsides:

- Free for user & developer

- Fast

- Multilingual

- Privacy baked in

- No network usage

- Relatively mature: less risk of accuracy churn

In theory, multimodal LLMs can handle OCR and understanding more variations of tickets layouts and bad lighting. In fact, while I was writing the parser, I used Opus 4.5 to read the test ticket images in order to create the ground truth test expectation data.

My issue with prototyping with LLMs further was that they had essentially the opposite pros and cons as the VisionKit system:

- Unknown, but some ongoing cost (meaning I’d need to come up with a monetization strategy before release)

- Unknown which level of model would correctly balance accuracy, cost, and speed over the short term.

- Requires network access

- Requires sending photo data off device (not hugely private, but still)

- Different outputs for the same input

What I didn’t explore directly was using the Apple Foundation model at the parsing layer. The current Apple Foundation model in iOS 26 has no image input API, but I could perhaps prompt it to take the raw output of the VisionKit model and try to make sense of it. My instinct is that this would be a waste of time, but still worth keeping on the table.

Overall strategy

While working on this, I honestly wasn’t thinking strictly in terms of prototype & production. From the first spark of idea I had an understanding of what the overall UX flow of the app would be. It was mostly getting to an answer of “is this feasible to productionize in a couple days?” while still being flexible on the scope of what production-ready meant.

That meant that I started by adding my ticket screenshot to the project, giving Claude my overall strategy, and having Claude create the OCR & parser system that output results directly into the UI.

OCR prototype

The first prototype parser supported just the two screenshots I had of Eki-net tickets (one from the morning of my trip; another from a similar trip a few months ago).

The implementation set up a VNRecognizeTextRequest in Japanese language mode, read out the highest ranking results into several lines of text ([String]), then fed that to Claude’s homegrown parser that pulled the ticket attributes out of that glob of text mostly using regex.

Since the input was from a perfectly legible screenshot, there was no issues with the VisionKit part nor the parser.

OCR for real Shinkansen ticket images

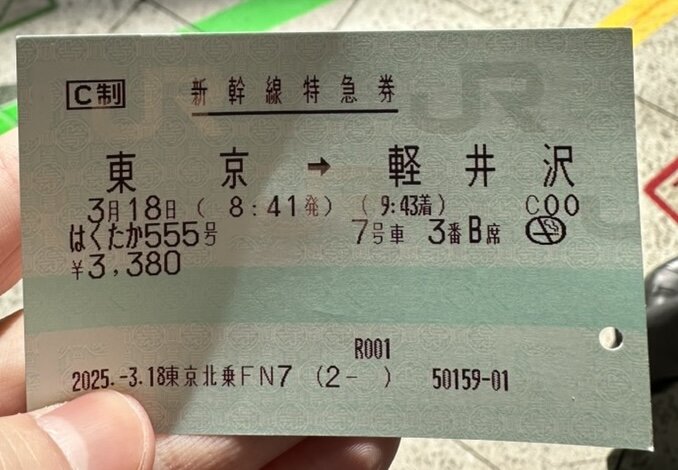

As soon as I tested the system on a real Shinkansen ticket in a photo, the system fell apart.

I searched through my personal Photo library for as many Shinkansen tickets as I could find. I googled for more. I started with 4 images (and later in development I ended up with about 10 images).

At first I was simply trying to naively patch out the parser with Claude. To do this, I set up a unit test system where I’d do the VisionKit request for each image once and write the resulting [String] data structure to disk. Then each unit test would read that data in, run the parser, and compare the expected ticket structure to the test result.

Unintuitively, the standard Swift Testing unit test setup was actually the less efficient way to iterate on this. Claude was having a lot of trouble reading the detailed test failure information after it ran xcodebuild in the command line. Each build & run & test iteration needed to boot up a fresh simulator, install the app, run the test, then tear down the simulator.

Instead, a built a @main App-based test harness that:

- temporarily disabled the real UI.

- ran the test code on

onAppear. - printed the test results via

printstatements. - called

exit(0)when finished.

For quickly prototyping, iterating, and understanding the scope of the problem space, this solved all the issues with the Swift Testing setup. The same booted simulator was reused on each run. DerivedData and build artifacts were reused, so builds were fast. Claude had no trouble reading print statements from the console output.

I let Claude run in its own loop for a while to see what it could and couldn’t improve with the parser based on the limitations of our system.

Claude found several underlying limitations with the VisionKit setup that were unsolvable at the parser level.

For example, concatenating all the text recognition objects into [String] was done somewhat naively by comparing y-coordinates. If the y-coordinates of objects were within a certain range, they were assumed to be on the same line. When the ticket was tilted, this strategy was interleaving text.

Additionally, some numbers and letters were just flat out being interpreted incorrectly. A 37 was read as a 30. CAR was read as CDR.

Off running on its own, Claude was trying to special case as much of these failure cases it could to get the tests passing.

CC制

東

3月18日(

はくたから5り考

¥3,380

新幹線特急券

京

→

8:41発)

軽井

(9:4着)

7号車

3番B席

R001

2025.-3.18東京北乗FN7(2-)

50159-01

沢

0

Comparing some of the fields, you can see the OCR output taken naively is not great:

- The departure time is there but the arrival time is

9:4instead of9:43. - The arrival station’s

軽井and沢are split up and should be軽井沢. - The departure station’s

東and京are split up and should be東京. - The train name and number are a mess:

はくたから5り考instead ofはくたか 555号

Using spatial data

The OCR part of the system was trying to abstract away the spatial parts from the parser. Looking at the raw data, my intuition was that the spacial data could be useful within the parsing layer. Instead of passing [String] between layers, I was now passing:

struct TextObservation: Equatable, Sendable {

let text: String

let x: Double

let y: Double

let width: Double

let height: Double

}

Each field parser within the parsing system could decide for itself how to use the spacial data. This is especially useful considering how important anchor values are. For example “発” (indicating a departure time) and “→” (indicating the station to the left is the departure station).

This improved things a bit for 5 ticket images, but after adding another 5 and going all in on English ticket support, there were plenty more edge cases to consider.

Transforms

Only after seeing some wonky positioning of the text boxes in my loading animation (see below), I realized that I wasn’t accounting for the image transform properly when converting the input UIImage to CGImage as input to VNRecognizeTextRequest.

extension CGImagePropertyOrientation {

init(_ uiOrientation: UIImage.Orientation) {

switch uiOrientation {

case .up: self = .up

case .upMirrored: self = .upMirrored

case .down: self = .down

case .downMirrored: self = .downMirrored

case .left: self = .left

case .leftMirrored: self = .leftMirrored

case .right: self = .right

case .rightMirrored: self = .rightMirrored

@unknown default: self = .up

}

}

}

Levenshtein distance

Like our previous example of CDR instead of CAR, VisionKit was reading strings like TOKIO instead of TOKYO. For these parts, I figured calculating Levenshtein distance from known strings was the right strategy. The Shinkansen system is large but not so large that I couldn’t ingest the station name values and the other known strings like JAN, FEB, etc.

One strategy I haven’t tested yet is using VNRecognizeTextRequest.customWords with the full dictionary of station names, etc. to see if that eliminates the need for using Levenshtein distance at all.

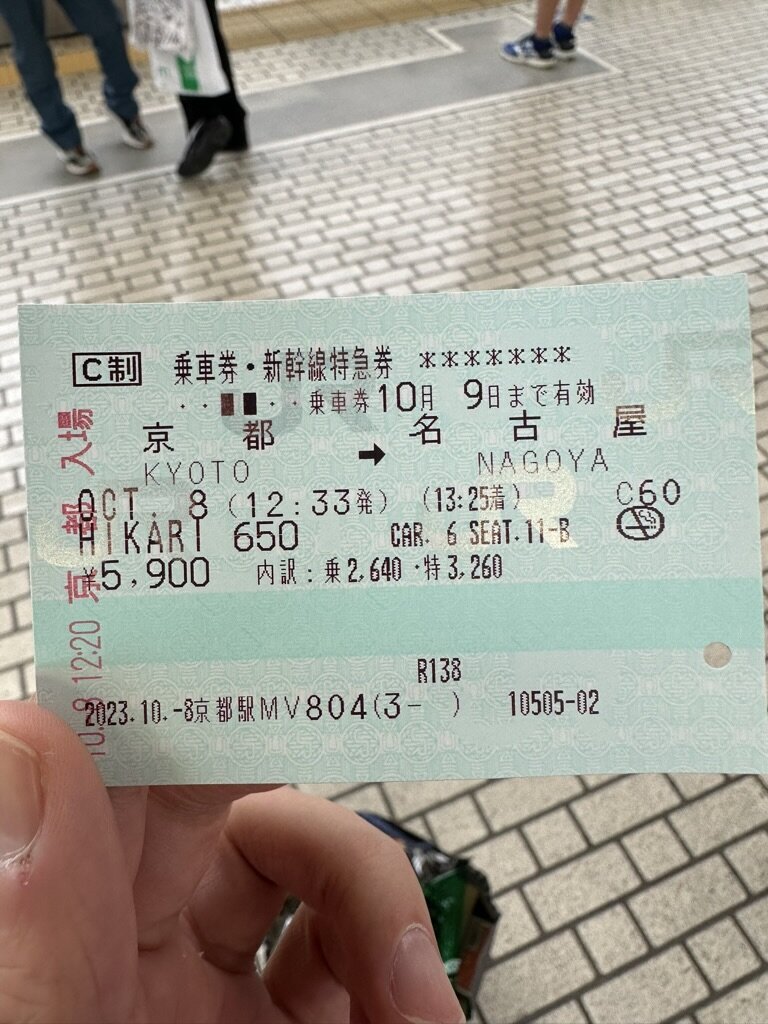

English and Japanese mode OCR

For some background, tickets can be printed in an “English” variant that includes a mix of English and Japanese text. If you buy from a ticket vending machine and complete the purchase in English mode, it’ll print an English ticket. Similarly, if you buy from a human ticket vendor at the counter, they will print your ticket in English variant if you speak English to them.

At the VisionKit layer, I was first using VNRecognizeTextRequest in Japanese-mode only.

I tried expanding a single instance to include both English and Japanese text. But checking the raw results, a dual language setup severely impaired its abilities.

For a while, I had a dual parsing system that would check for a few English strings, and if any were found, it would assume the ticket was an “English ticket” and run a separate English VNRecognizeTextRequest and return those results. This didn’t work well for a few reasons:

- The Japanese

VNRecognizeTextRequestwas surprisingly bad at reading numbers compared to the English one. - Deciding at the VisionKit layer which text results should come from the English request didn’t make a lot of sense conceptually if I wanted to keep the majority of the logic in the parser layer.

Therefore, I decided to run both the English and Japanese VNRecognizeTextRequests on every input and provide all the results to the parser.

struct BilingualOCRResult: Sendable, Equatable, Codable {

let jp: [TextObservation]

let en: [TextObservation]

}

I was also previously discarding the confidence score (0.0...1.0) that VisionKit provides with each observation. This score was actually different in the parallel observations for English and Japanese in some cases, especially number recognition. I added the confidence score to the output so the parser could use it.

struct TextObservation: Equatable, Sendable, Codable {

let text: String

let x: Double

let y: Double

let width: Double

let height: Double

var confidence: Float

}

Unparseable fields fallback UX

At this point in the development of the parser, I was pretty certain reading photos of tickets was never going to be reach 100% accuracy for every field.

I took a break from working on the parser to implement editing for every field in the ticket UI. This meant that users could manually recover from parsing errors and omissions.

Not needing to reach 100% accuracy in the parser while still ensuring the user gets value out of the system as a whole opened up a more reasonable strategy for the parser.

Defense-in-depth parsing system

After tweaking more and more of the VisionKit layer, I had to regenerate the VisionKit output test data for each test ticket image, and then essentially rewrite the parser layer.

This time, the strategy was to:

- Pass in the full English and Japanese results including relative x and y coordinates to each field.

- Create a sub-parser dedicated to each field of the ticket that needed to be parsed.

Within each sub-parser, my strategy was to start with the best case scenario of input data quality, then step-by-step keep loosening the guidelines to account for more unideal cases that had come up in the test data, then finally falling back to returning nil for that field.

OCR testing system

Claude iterated on the field parser implementations for an hour or two, one at a time, checking the test output to ensure there were no regressions along the way.

At a certain point all the tests were passing and as much as I wanted to keep finding test data and tweaking the parser, I knew I had to move on.

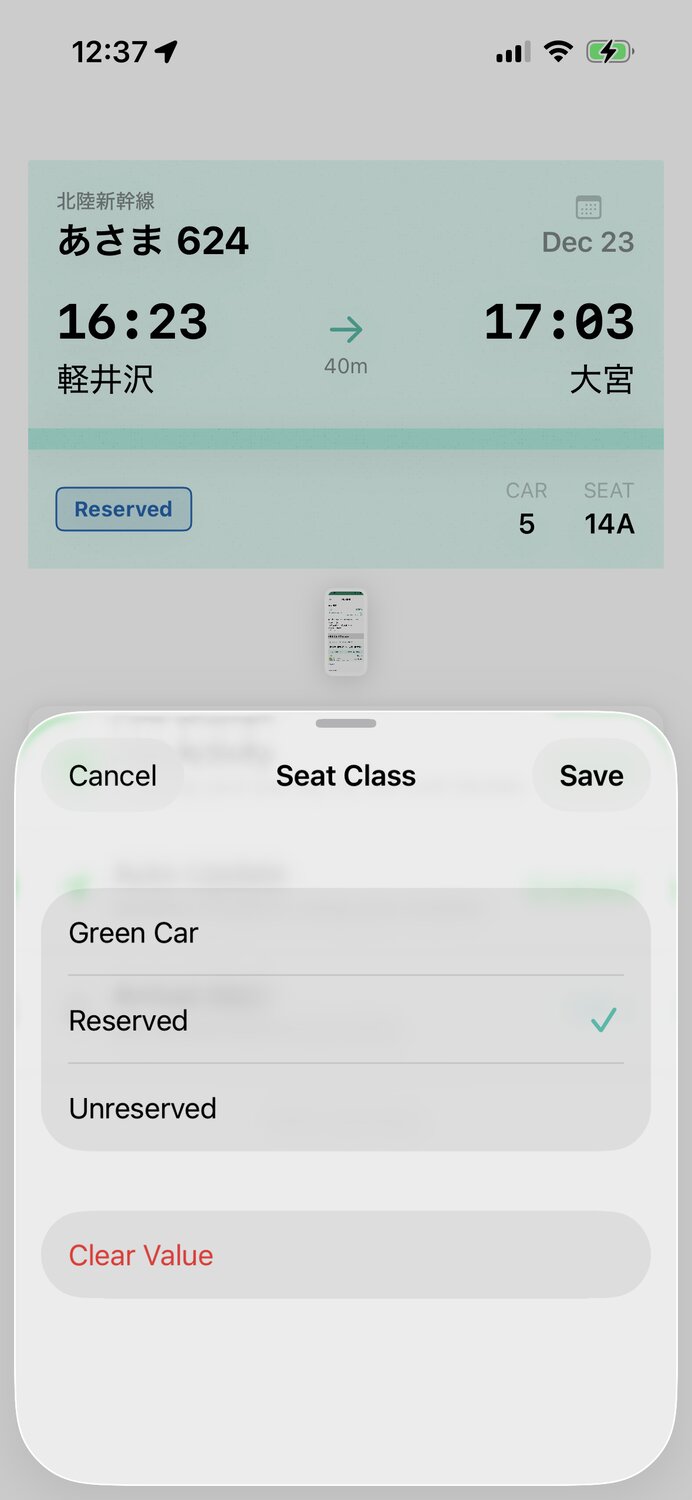

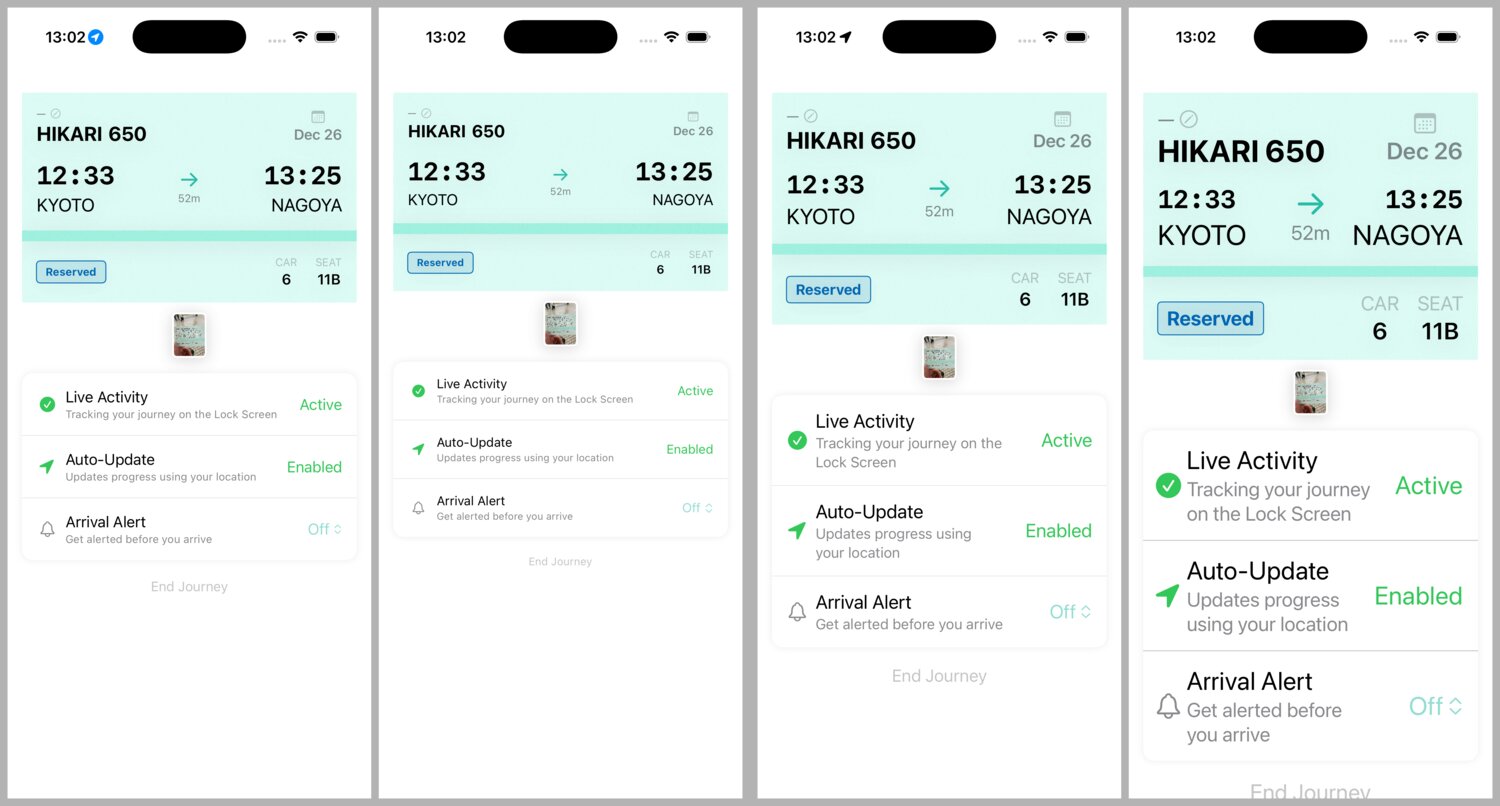

Live Activities

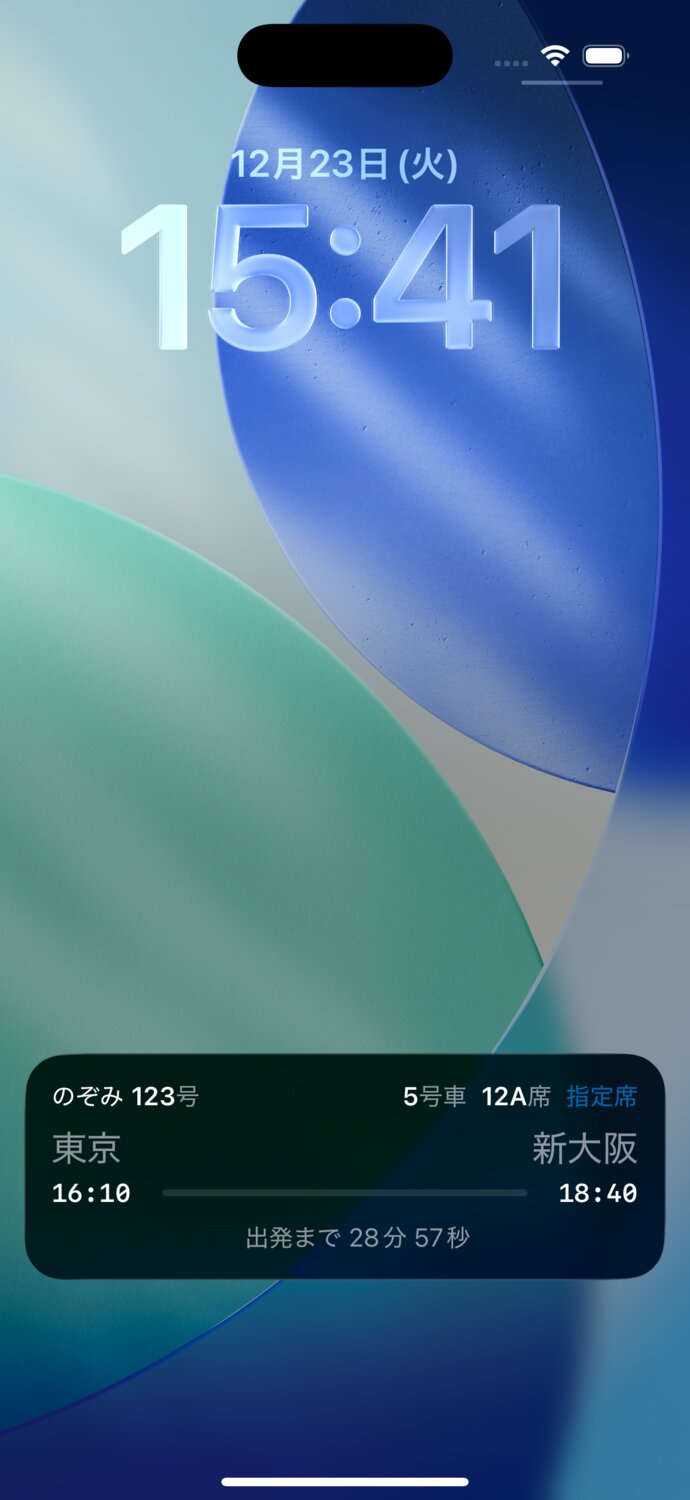

During development I had to keep reminding myself that the whole point of this endeavor was to have a slick (read: useful) Live Activity.

My design process was quick and to-the-point:

- list out all the Live Activity contexts: lock screen, dynamic island compact leading, compact trailing, minimal, and expanded.

- consider all the ticket info I had available from the parser output.

- consider all of the above for the “before” and “during” trip phases (if I knew I had more accurate control over Live Activity update timing, I might have divided these phases up even further).

In lock screen and expanded contexts, you can mostly display everything you want. The challenge is in aesthetics and visual hierarchy like in any design.

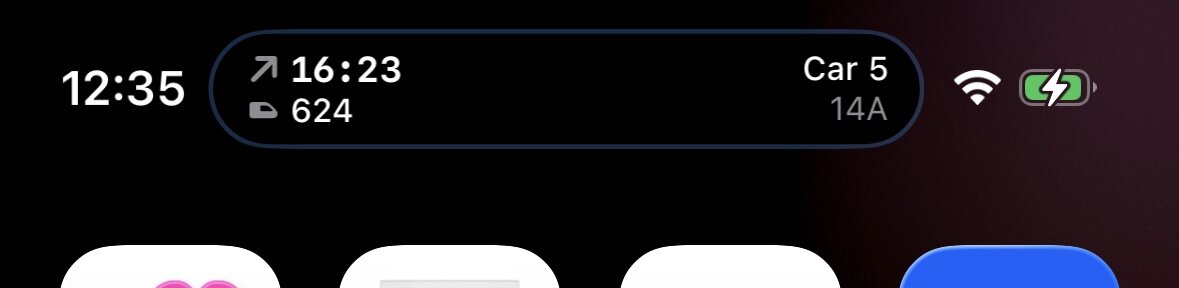

When dealing with the compact and minimal contexts, you really do only have the equivalent of about 6 very small characters to work with, and 2 lines if you want to push your luck. If you try to fill the entire available space of the Dynamic Island on either side, you’ll lose the system clock which is no go for my use case.

When I thought about it, the most important of all the contexts was the compact leading and trailing in the before trip phase. This is when the information is most needed at a glance.

I stacked in departure time and train number in the compact leading. This information is used to decide when to go to the platform and which platform to go to.

I stacked the car and seat number in the compact trailing. These are used to decide where to line up on the platform and of course where you’ll sit.

View guidelines and tips

Designing for Live Activities is painful. There are significantly more constraints to the SwiftUI View system than in normal app contexts. Most are undocumented. Some quirks can be teased out in the SwiftUI Preview if you’re lucky. Others only appear on the simulator or a real device.

I have a couple guidelines and tips I follow for Live Activities.

Use non-semantic font sizes for compact and minimal

The system ignores Dynamic Type settings in the compact and minimal Dynamic Island contexts. Using point sizes directly gives more flexibility while designing in the very limited space.

In the lock screen and expanded contexts, there’s limited Dynamic Type support (4-levels total), so it’s still worth using semantic fonts as usual (e.g. .headline, .title3).

For dynamically updating times, prepare to spend a lot of time in trial and error

Maybe someday I’ll write a full explainer post on which countdown-style Text fields are supported. In short, if you want dynamically updated fields in any part of your Live Activity, your formatting options are limited and underdocumented.

A couple configurations I used:

// `44 min, 23 sec` or `1 hr, 52 min`

Text(attributes.departureTime, style: .relative)

// Centers `Departing in N min, M, sec` due to `.relative`'s implicit `maxWidth: .infinity`

HStack(spacing: 4) {

Text(String(localized: "widget.departing-in", comment: "Footer label shown before departure"))

.frame(maxWidth: .infinity, alignment: .trailing)

Text(attributes.departureTime, style: .relative)

}

// Linear progress view with no label

ProgressView(timerInterval: attributes.departureTime ... attributes.arrivalTime, countsDown: false)

.progressViewStyle(.linear)

.labelsHidden()

// `60:00`

Text(

timerInterval: (Date.now)...(Date(timeIntervalSinceNow: 60*60)),

pauseTime: Date(timeIntervalSinceNow: 60*60),

countsDown: true,

showsHours: false

)

As noted above, any Text using: Text(Date(), style: .relative) will expand to fill its full width.

It’s frustrating just thinking about this again. I basically just banged my head against the wall until I landed on a design I felt embarrassed but comfortable shipping.

Clamped width custom Layout

I use this custom Layout judiciously in the Dynamic Island.

It makes the underlying view’s frame collapse to fit its ideal width, but clamped to a maximum value.

I want the compact or minimal context to be as narrow as possible. I want short input text to result in a very narrow Dynamic Island layout. I want longer input not to expand beyond a certain width; and even more, I want to use the minimumScaleFactor modifier to further shrink the text size once that maximum width is reached.

private struct SingleViewClampedWidthLayout: Layout {

var maxWidth: CGFloat

func sizeThatFits(proposal: ProposedViewSize, subviews: Subviews, cache: inout Void) -> CGSize {

guard let subview = subviews.first else { return .zero }

let idealWidth = subview.sizeThatFits(.init(width: nil, height: proposal.height)).width

let width = min(idealWidth, maxWidth)

return subview.sizeThatFits(.init(width: width, height: proposal.height))

}

func placeSubviews(in bounds: CGRect, proposal: ProposedViewSize, subviews: Subviews, cache: inout Void) {

guard let subview = subviews.first else { return }

subview.place(at: bounds.origin, proposal: .init(bounds.size))

}

}

private struct ClampedWidth: ViewModifier {

let maxWidth: CGFloat

func body(content: Content) -> some View {

SingleViewClampedWidthLayout(maxWidth: maxWidth) {

content

}

}

}

extension View {

@ViewBuilder func clamped(maxWidth: CGFloat) -> some View {

modifier(ClampedWidth(maxWidth: maxWidth))

}

}

Updating in background

Live Activities can usually only be updated via remote Push Notification. But if your app gets a chance to wake up and run in the background, it can also issue updates to the Live Activity.

One of the few reliable ways to have your app woken up in the background regularly is to use significant location updates from Core Location. In order to have your app get background time you need to:

- Be approved by the user for

AlwaysLocation Services permission. - Be approved by the user for

WhenInUseLocation Services permission AND one of the following- Have an active Live Activity OR

- Start a CLBackgroundActivitySession (that essentially creates a default Live Activity)

In the case of Shinkansen Live, I have two phases for the Live Activity:

- before the train departs

- after the train departs

The time of that change over is pretty reliably scheduled. But Live Activities have no update schedule like Widgets do (for some reason).

To update the Live Activity after the train departs I could:

- Have the user tap a button in the lock screen or expanded Live Activity that triggers an intent to wake up the app in the background and update the Live Activity.

- Hope the user opens the app on their own.

Both of these options are unideal, so instead I ask for WhenInUse Location Services permission and start a monitoring for significant locations. One of these will be fired not long after the train departs (within about 1km or 5 minutes). That trigger will open the app in the background, update the Live Activity based on the current time, then go back to sleep.

Persisting the trip

There’s an edge case I wanted to handle with the Live Activity lifetime.

If the system kills the app in the middle of a trip, the Live Activity in theory should continue uninterrupted since it’s an App Extension. But in the case of Shinkansen Live, I’m expecting to update the Live Activity while the app is backgrounded. This means there’s a potential flow where:

- The app is in the background with the Live Activity running.

- The app is killed by the system.

- The Live Activity continues to run.

- The system cold launches the app in the background.

At this point, I could decide to query the Live Activities framework to see if there’s a Live Activity running and if so, restore the ticket model layer and UI. However, I prefer not to treat the Live Activity as the source of truth for the model layer.

I added support with the Sharing library to persist the ticket model automatically on changes. On the above flow, I use the persisted ticket model to restore the UI and Live Activity and AlarmKit state, ensuring the ticket data is still valid.

Handling dismissal

One final bit of UX that’s not mission critical but is very user friendly is to respond to user-initiated Live Activity dismissals from the lock screen. If the user swipes from right to left on your Live Activity, the system dismisses it. When your app next runs, it will receive an update from Activity.activityStateUpdates stream (if you’re monitoring it).

If the app detects a user-initiated dismissal, I consider that their trip has ended, clear the ticket, and go back to the app home screen. There’s an argument that it’d be safer to simply toggle the Live Activity, but since my app’s only purpose is to show a Live Activity, I don’t think it makes sense to build in more complexity to keep multiple states.

Animations

The focused nature of this app allowed me a bit more breathing room to experiment with custom screen transitions and multi-stage animations.

Root level transitions

At the bare minimum, I usually try to use a default opacity transition for root level views when they aren’t covered by system transitions like a navigation push or sheet presentation.

For Shinkansen Live, I added a little bit of extra scale effect to the usual opacity transition of the initial screen, both on cold launch and when returning from the trip screen.

For the trip screen, I first animated the card down from the top with some scale and opacity, then fade in the other sections with some scale.

Scanning animation

The most fun was doing the scanning animation. Once the selected image is downloaded and displayable, I animate it in with a bit of 3D effect. Then I use the coordinate results of the text observations to animate those boxes onto the image.

This animation serves a few purposes in my opinion:

- Visually expresses to the user what the app is actually doing.

- Buys time for the parser to do its job.

- Feels fun and playful in a way that is motivating for users to want to go through the trouble of submitting their ticket image.

Ticket image modal animation

My final bit of (self) user testing made me realize that even though I’d built in a way to update ticket values that were missing or erroneously parsed, I had no in-app UI for actually doing the field checking. Depending on their input source, the user would have to hold up their physical ticket next to the app’s virtual ticket to double check the fields. Or if they’d used a screenshot, they’d have to flip back and forth between Photos app.

As my last big task, I added support for showing the original image inline with the ticket in a modal overlay.

This setup uses matchedGeometryEffect and was a nightmare to work through. In the end it’s not perfect, but the speed conceals some of the jankiness. matchedGeometryEffect has a lot of undocumented incompatibilities with other modifiers, so it was just hours upon hours of reordering modifiers and building and running to check what had changed. I came out of the experience with little new demonstrably true observations I can share here, unfortunately.

Card dragging

Whenever there’s a card-looking UI on screen, I want it to be interactable even if there’s no real gesture that makes sense.

I created a custom drag gesture with rubberbanding that allows the user to drag the ticket a little bit in any direction. When released, it snaps back with a custom haptic that mirrors the visual.

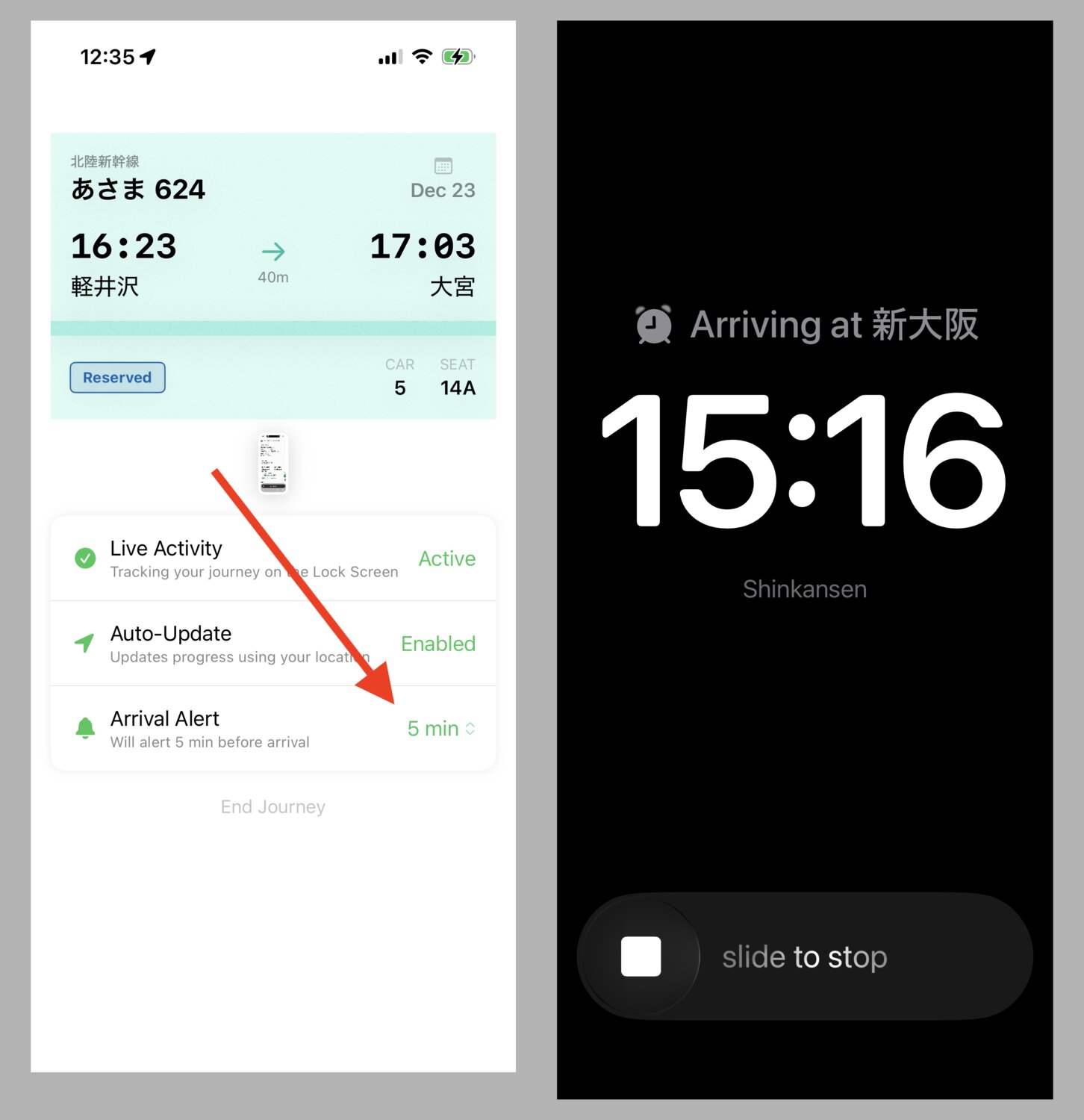

AlarmKit

AlarmKit is new in iOS 26 and I thought it might be a good fit for Shinkansen Live’s use case.

The integration was mostly straightforward, but it added another layer of complexity to the reducer implementation to ensure that it was added, changed, and removed for all the relevant cases:

- Arrival time exists or doesn’t exist.

- Arrival time is updated manually by the user.

- System time is too close to arrival time to set an alarm.

- Journey is ended by the user before arrival time.

- Live Activity is dismissed from the lock screen.

And more.

Permission dialog

A last minute annoyance with AlarmKit was testing localization: I found a bug where the localized text for the AlarmKit permissions dialog was not being used on iOS 26.0. But the bug was fixed for iOS 26.1. And no, the bug nor the fix were mentioned in any official SDK release notes.

Localization

One of my favorite usages for coding agents is doing Localization setup. Note I’m specifically not talking about LLMs doing the actual translation, but instead:

- doing the initial conversion from inline strings to string keys e.g,

loaded.end-journey-button. - adding localizer comments to each string key e.g.

Button to end the current journey. - maintaining default values for when string interpolations are required e.g.

Button(

String(

localized: "loaded.arrival-alert.status.minutes-before",

defaultValue: "\(mins) min before",

comment: "Status showing minutes before arrival (for menu items)"

)

) { ... }

The initial conversion uses a custom markdown document with some basic rules. It takes about an hour for the first run and then a few more passes with a human in the loop to ensure the xcstrings file is clean.

Dynamic Type

The app still lays out pretty well with most levels of Dynamic Type. I only use semantic font qualifiers. All content is in a scroll view that’s usually fixed.

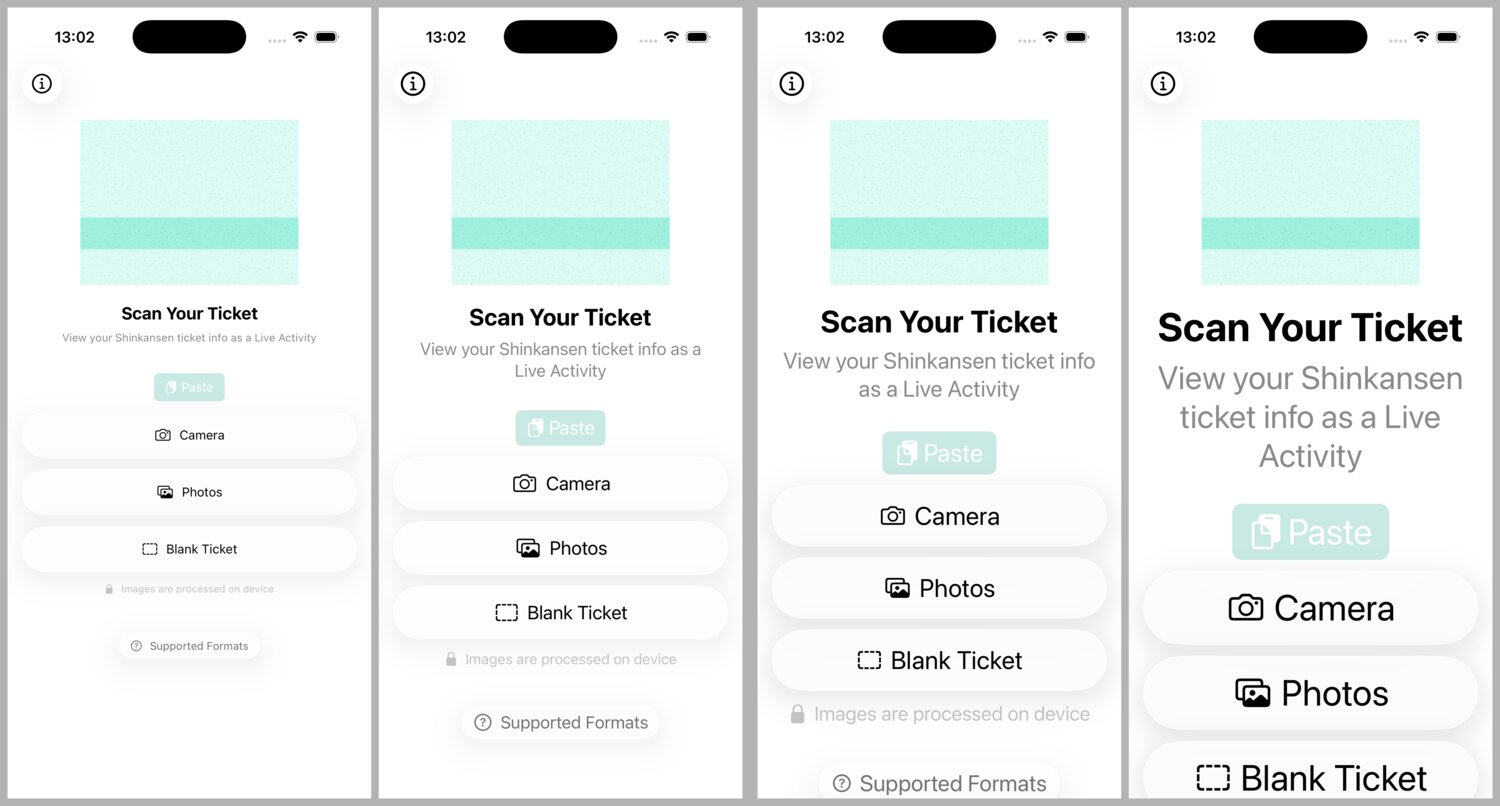

VisionKit Camera

I’m using VNDocumentCameraViewController as the integrated camera view for scanning. The UX is a little weird because there’s no way to limit the input (output?) to one photo. The result is the user can take a bunch of photos of their ticket before they tap “Done” and the app will only read the first.

Project stats

By the numbers

- Development time: ~6 days including App Store materials

- Lines of Swift (excluding tests, static data, etc.): 8,388

Daily Devlog

- Dec 16, 2025 — Initial layout & OCR foundation

- Dec 17, 2025 — Live Activities, AlarmKit, failure states

- Dec 18, 2025 — Bilingual OCR, loading animation, app icon, localization

- Dec 19, 2025 - Parser rewrite, settings view

- Dec 20, 2025 — Polish, persistence, supported formats view, App Store prep

- Dec 23, 2025 — Ticket image modal, App Store materials, v1.0 Release

Conclusion

Part of the appeal of this idea is that the scope could only creep so much. I honestly didn’t leave much on the TODO list for a version 1.1 besides endless optimization potential for the parser.

As usual this post was brain-dump style. If there’s any part you connected with and would like me to explore further, feel free to give me a shout.